Often, the Golang programs we create are not just REST-API servers, but also include other functions such as Event Consumers, Schedulers, CLI Programs, Database Backfills, or combinations of all of them. This project structure guideline can be used to enable all of that. This structure focuses on separating core logic from external dependencies, allowing code reuse across various application modes.

Repository Link: https://github.com/muchlist/templaterepo

Principles and Goals:

- Development Consistency: Providing uniform methods in building applications to improve team understanding and collaboration.

- Modularity: Ensuring code separation between modules and avoiding tight coupling, making maintenance and further development easier.

- Effective Dependency Management: Avoiding circular dependency errors despite having many interconnected modules, through applying dependency inversion principles.

- Testable Code: Applying Hexagonal architecture principles to separate core logic from external dependencies, thereby improving flexibility and ease of testing.

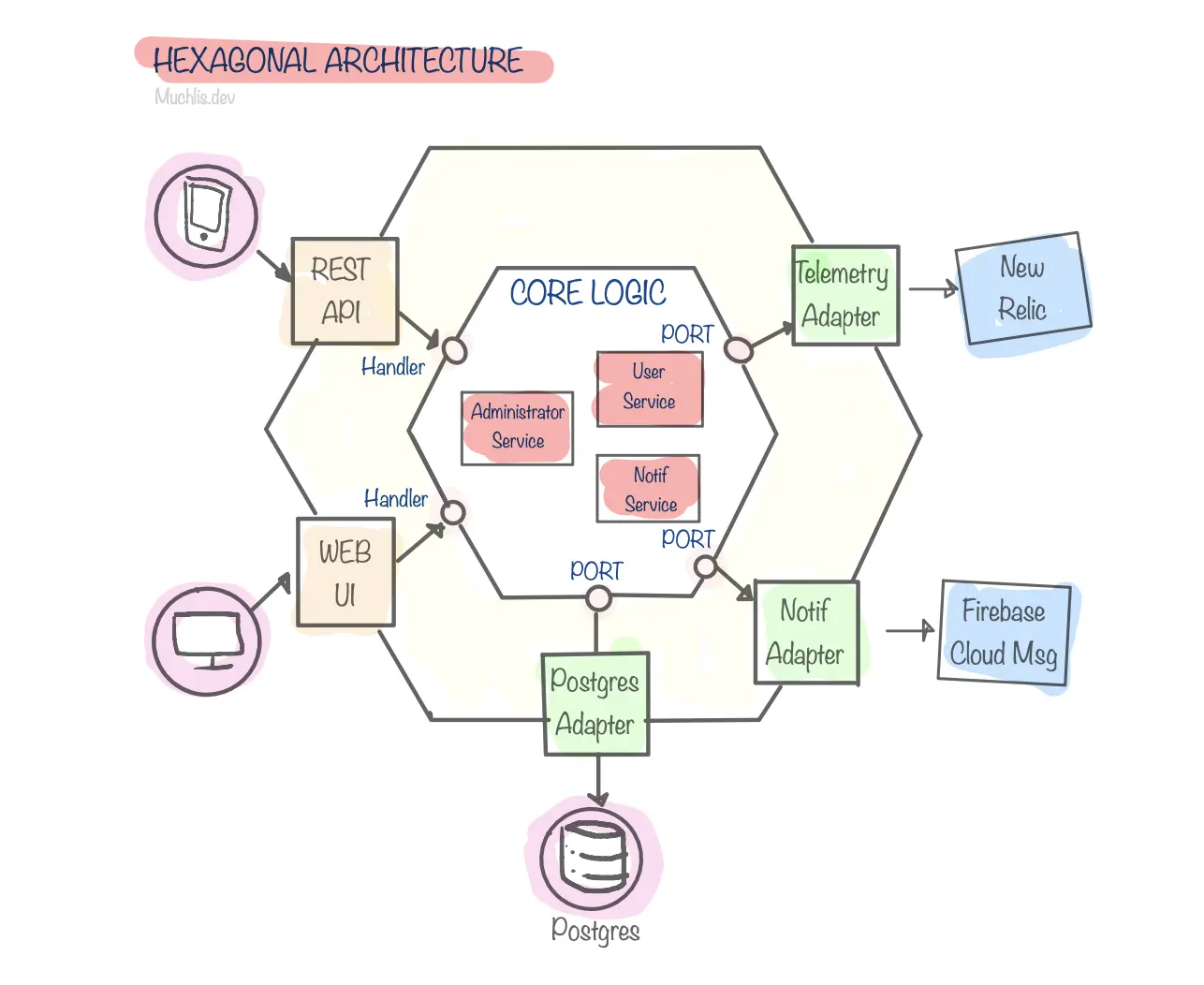

Conceptual Hexagonal Architecture

Hexagonal architecture, also known as ports and adapters architecture, focuses on separating core logic from external dependencies. This approach supports the design principles mentioned above by ensuring that the application core remains clean and isolated from external components.

Core: Contains the application’s business logic.Ports: A collection of abstractions that define how external parts of the system can interact with the core. Ports can be interfaces used by the core to interact with external components such as databases, notification providers, etc. I usually use Golang idioms in naming these interface types likestorer,reader,saver,assumer.Adapters: Implementations of ports. Adapters implement the interfaces defined by ports to connect the core with external components.

Project Structure

├── app

│ ├── api-user

│ │ ├── main.go

│ │ └── url_map.go

│ ├── consumer-user

│ │ └── main.go

│ └── tool-logfmt

│ └── main.go

├── business

│ ├── complex

│ │ ├── handler

│ │ │ └── handler.go

│ │ ├── helper

│ │ │ └── formula.go

│ │ ├── port

│ │ │ └── storer.go

│ │ ├── repo

│ │ │ └── repo.go

│ │ └── service

│ │ └── service.go

│ ├── notifserv

│ │ └── service.go

│ └── user

│ ├── handler.go

│ ├── repo.go

│ ├── service.go

│ ├── storer.go

│ └── worker.go

├── conf

│ ├── conf.go

│ └── confs.go

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

├── migrations

│ ├── 000001_create_user.down.sql

│ └── 000001_create_user.up.sql

├── models

│ ├── notif

│ │ └── notif.go

│ └── user

│ ├── user_dto.go

│ └── user_entity.go

└── pkg

├── db-pg

│ └── db.go

├── errr

│ └── custom_err.go

├── mid

│ └── middleware.go

├── mlog

│ ├── log.go

│ └── logger.go

└── validate

└── validate.go

Folder: app/

The App folder stores code that cannot be reused. The focus of code in this folder includes:

- The starting point of the program when executed (starting and stopping the application).

- Assembling dependency code required by the program.

- Specific to input/output operations.

In most other projects, this folder would be named cmd. It’s named app because the folder position will be at the top (which feels quite good) and adequately represents the folder’s function.

Instead of using frameworks like Cobra to choose which application to run, we use the simplest method such as running the program with go run ./app/api-user for the API-USER application and go run ./app/consumer-user for the KAFKA-USER-CONSUMER application.

Folder: pkg/

Contains packages that can be reused anywhere, usually basic elements not related to business modules, such as logger, web framework, or helpers. A place to put libraries that have been wrapped to make them easy to mock.

Both application layer and business layer can import this pkg.

Using pkg/ as a container for code that you initially weren’t sure where to place has proven to speed up the development process. Questions like "Where should I put this?" will get the default answer "Put it in pkg/.".

Folder: business/ or internal/

Contains code related to business logic, business problems, business data.

Folder: business/{domain-name}/*

In each business domain, there’s a service layer (or core in hexagonal terms) that must remain clean from external libraries. This includes layers for accessing persistent data (repo) and interfaces that function as ports.

Folder: business/{domain-name}/{subfolder}

Sometimes, a domain can become very complex, requiring separation of service, repo, and other elements into several parts. In such cases, we prefer to organize and separate these components into different folders, which will also require using different packages. For example, business/complex.

Folder: models

Models (including DTOs, Payloads, Entities) are usually placed within their respective business packages. However, in complex cases where application A needs models B and C, we can consider placing these models at a higher level so they can be accessed by all parts that need them.

Separating structs between Entity, DTO, and Model is quite important to maintain flexibility and code cleanliness. This is because:

- What is consumed by business logic will not always be exactly the same as the database model.

- The response received by users will not always be exactly the same as the database table. And so on.

Read: Understanding the Importance of Separating DTO, Entity and Model in Application Development

Rules

It’s very important to create and update agreed-upon rules so that all parties follow a consistent approach. For example, this repository template is based on its ability to avoid tightly-coupled code, so the Code Dependency Writing Rules become very important to follow.

These rules will grow over time. For example, what often causes disagreement:

How deep should if-else conditions be allowedHow to perform database transactions in the logic layer?. And so on.

Also read Database Transaction Implementation Techniques in Logic Layer for Golang Backend

Code Dependency Writing Rules

Using Dependency Injection:

Dependency Injection (DI) is a design pattern where dependencies are provided from outside the object. This helps manage dependencies between components, makes code more modular, and facilitates testing. So, modules that depend on each other must depend on abstractions.

Example constructor for creating user service logic business/user/service.go

type UserService struct {

storer UserStorer

notifier NotifSender

}

// NewUserService requires UserStorer and NotifSender.

// UserStorer and NotifSender are abstractions required by UserService

// Objects that will fulfill UserStorer and NotifSender will be determined by

// dependency configuration in the /app folder.

// UserStorer and NotifSender can also be mocked for easy testing

func NewUserService(store UserStorer, notifier NotifSender) *UserService {

return &UserService{storer: store, notifier: notifier}

}

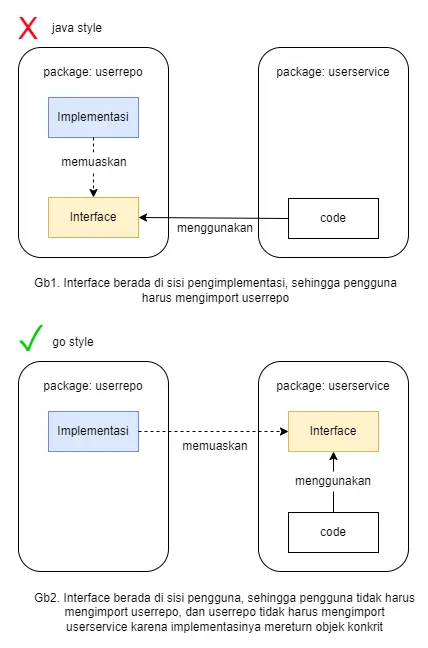

Applying Dependency Inversion Principle:

In the business layer, especially for the logic part (usually named service.go or usecase.go or core), communication between layers relies on abstractions and strong application of the dependency inversion principle. In Golang, true dependency inversion can be achieved as explained in the following diagram.

Regarding interface positioning, it’s best to place them in the module that needs them. This has been discussed in the book 100 Go Mistakes and How to Avoid Them and several other books.

For example, the business/user domain needs a function to send notifications that can be fulfilled by business/notifserv, but business/user doesn’t explicitly say it needs business/notifserv, but rather says "I need a unit that can execute SendNotification()" – period.

The dependency implementation can be seen in app/api-user/routing.go. This method prevents circular dependency import errors and ensures code remains loosely coupled between domains.

Example dependencies needed to create user core logic business/user/storer.go:

package user

import (

"context"

modelUser "templaterepo/models/user"

)

// UserStorer is an interface that defines operations that can be performed on the user database.

// This interface belongs to the service layer and is intended to be written in the service layer part

// Although we know exactly that the implementation is in business/user/repo.go, the service layer (core) still only depends on this interface.

// The concrete implementation of this interface will be determined by dependency configuration in the /app folder.

type UserStorer interface {

Get(ctx context.Context, uid string) (modelUser.UserDTO, error)

CreateOne(ctx context.Context, user *modelUser.UserEntity) error

}

// NotifSender is an interface that defines operations for sending notifications.

// This interface belongs to the service layer and is intended to be written in the service layer part

// The object used to send notifications will be determined by dependency configuration in the /app folder.

type NotifSender interface {

SendNotification(message string) error

}

Example constructor for creating notification business/notifserv/service.go

package notifserv

type NotifService struct{}

// return concrete struct, not its interface

// because NotifService is not constrained to only be NotifSender

func NewNotifServ() *NotifService {

return &NotifService{}

}

// SendNotification is required to fulfill the NotifSender interface in user service

func (n *NotifService) SendNotification(message string) error {

// TODO : send notif to other server

return nil

}

// SendWhatsapp is not required by user service but might be needed by other services

func (n *NotifService) SendWhatsapp(message string, phone string) error {

// TODO : send whatsapp

return nil

}

Other Agreed Rules

- Follow Uber’s style guide as a base (https://github.com/uber-go/guide/blob/master/style.md). This rule will be overridden if there are rules written here.

- Configuration files should only be accessed in main.go. Other layers that want to access configuration must receive it through function parameters.

- Configuration must have default values that work in local environment, which can be overridden by

.envfiles and command line arguments. - Errors must be handled only once and must not be ignored. This means either consume or return, but not both simultaneously. Example consumption: writing error to log, example return: returning error if error is not nil.

- Don’t expose variables in packages. Use combination of private variables and public functions instead.

- When code is widely used, create helper.go. But if used in several packages, create a new package (for example to extract errors that only exist in user,

/business/user/ipkg/error_parser.go). If usage is very broad, put it in/pkg(for example,pkg/slicer/slicer.go,pkg/datastructure/ds.go,pkg/errr/custom_error.go). - Follow Golang idioms. Name interfaces with -er or -tor suffixes to indicate they are interfaces, such as Writer, Reader, Assumer, Saver, Reader, Generator. (https://go.dev/doc/effective_go#interface-names). Example: In a project with three layers: UserServiceAssumer, UserStorer, UserSaver, UserLoader.

Tools

Makefile

Makefile contains commands to help run applications quickly because you don’t have to remember all the long commands. Functions like aliases. The way is to write commands in the Makefile like the following example.

The top line is a comment that will appear when calling the helper.

.PHONY is a marker so the terminal doesn’t consider makefile commands as file access.

run/tidy: is an alias for the commands inside it.

## run/tidy: run golang formatter and tidying code

.PHONY: run/tidy

run/tidy:

@echo 'Tidying and verifying module dependencies...'

go mod tidy

go mod verify

@echo 'Formatting code...'

go fmt ./...

As an example, to run the applications in this repository we can use commands like below:

# 1. ensure availability of dependencies like database etc.

# 2. run application with makefile (see Makefile)

$ make run/api/user

# that command will execute

$ go run ./app/api-user

# so the http server mode of the application will be run

pre-commit

It’s recommended to use pre-commit (https://pre-commit.com/).

// init

pre-commit install

// precommit will be triggered every commit

// manual

pre-commit run --all-files